Here’s SBY’s bedside read

|

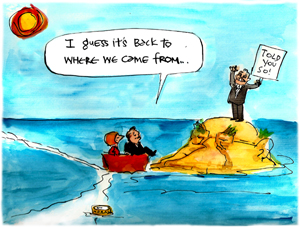

| Attack on Ahmadiyah compound (International Crisis Group) |

What sort

of liberty must a good society give to members of minorities whose religion the

majority finds incorrect, or even sinful and bad? What limits could a decent society impose on religious behavior?

These

questions, articulated by American philosopher Martha Nussbaum in The New

Religious Intolerance, confronted settlers in the United States in the 17th

century. Many were escapees from

mainstream religious persecution in the Old World, determined to fashion a

fresh social order.

The issues

surfaced again in 1945 when Soekarno rejected hardliners seeking to impose

Sharia law. He needed the minority

Christians, Hindus and Buddhists on board to launch the new nation in a world

tired of religious conflict, praying for an example of accord.

The

questions remain valid today as the Presidential Palace ponders the right

response to attacks on churchgoers in Bogor and Bekasi. Then there’s

persecution of Shiites and Ahmadiyahs trying to sustain their belief in Chapter

XI of the Constitution - the section guaranteeing religious freedom for

all.

In seeking

solutions to these questions President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono and his

advisers could enrich their decision-making by reading this book and mull over

its central idea – that fear drives hate, and little will change till this is

understood and confronted.

What sort

of fear? Professor Nussbaum (she teaches law and ethics at the University of

Chicago) includes primitive anxieties about the unknown, and threats of

difference driven by ignorance.

Heading the

list is Islamophobia, the black death of reason and respect, infecting the West

in ways that lead voters and legislators to react irrationally.

In

Switzerland, a nation famed for its prosperity and independence, a referendum

resulted in a ban on mosque minarets.

Only five per cent of the population is Islamic. The restriction was opposed by the

Parliament, Jewish communities and Catholic bishops, but 57 per cent of the population,

stoked by agitators using cartoons that made the minarets look like missiles,

voted to prohibit.

France and

Italy (centers of world fashion) have banned burkas even though only a wisp of

women choose this dress – one estimate is under 3,000.

In the US

and Britain the media immediately assumed that last year’s massacre in Norway

that took 76 lives was the work of Al Qaeda. Later we learned the gunman was a psychopath

hating Muslims.

In the US

there are too many stories to list here of travellers with Islamic names and

‘Middle-Eastern appearance’ being targeted by zealous immigration officials.

Then

there’s the case of Park 51, the Islamic proposal to build a multi-faith

community center close to Ground Zero, the site of the twin towers destroyed in

2001.

It wasn’t a

mosque, though it did include prayer space.

The controversy features heavily in this book as an example of the need

for informed leadership, to comment with care and to never let such debates get

hijacked by demagogues.

At first

people supported the center and saw no harm.

Then a campaign of hate and lies began and what the author calls the

‘cascade’ of hostility, with people rushing to join others who claim to know

the truth.

The

proposers weren’t faultless. Comments Professor Nussbaum: “Park 51 was a set of

good ideas too hastily put forward with too little clarification of goals and

concepts, and much too little consultation with the local community.”

At the

start of the 2010 Ramadhan President Barack Obama, a skilled orator and

wordsmith, said “… I believe that Muslims have the same right to practise their

religion as anyone else in this country.”

However a

day later he “clarified” his position saying he was only commenting on the

constitutional question, not “the wisdom of making the decision to build a mosque

there.” Presidential prevarication

isn’t exclusive to Indonesia.

Two

stand-outs make this book valuable. The

author writes with clarity, rare for an academic. She’s also a moderate, pragmatic

about the need for tough security measures but arguing these must be based on

the unbiased presentation of facts.

Till

recently the FBI taught recruits about Islam using writings varying from the

questionable to the grossly bigoted. Simplistic clichés smothered truths. The difference between Sunni and Shiite was

misrepresented or ignored. So was the

fact that Indonesia and India have the world’s largest populations of

Muslims.

The author

concludes “that the suspicion and mistrust of academic scholarship by the FBI

that began during the McCarthy era have never really ended.”

In the

interfaith business it’s easy to get depressed. Just when imams and bishops

shake hands the warped ones decide that hate is better than harmony. All the fine words are blasted apart and

it’s start-over time again.

The

fearmongers move in with disguised agendas, their half-truths and untruths fill

the hole left by the ditherers, and the rat is off and running. There’s no rest

for the righteous.

The Greek

philosopher Socrates advocated the ‘examined life’ with a democracy “thoughtful

rather than impetuous, deliberative rather than unthinkingly adversarial.”

Sounds

good, but there’s a catch, as the author reveals:

“The

insight that Socrates lacked was that politics and government have no business

telling people what God is or how to find the meaning of life.

“Even if

governments don’t coerce people, the very announcement that a given religion

(or anti-religion) is a preferred view is a kind of insult to people who in all

conscience cannot share this view.

“That’s a

point that Socrates and many philosophers after him, have utterly failed to

understand.”

The New

Religious Intolerance

Martha C

Nussbaum

Harvard

University Press 2012

(First published in The Sunday Post, 22 September 2012)

##