No sex please – we’re Indonesians

For rationalists it’s screamingly obvious: Sex without consent is rape and a criminal offence which all should know. Though to Indonesian fundamentalists that’s a shortcut to immorality.

Indonesians like visually polluting public places with spanduk (banners). Those degrading the streetscape are usually adverts for smokes, but on university campuses they carry practical info about enrolments and guest lectures.

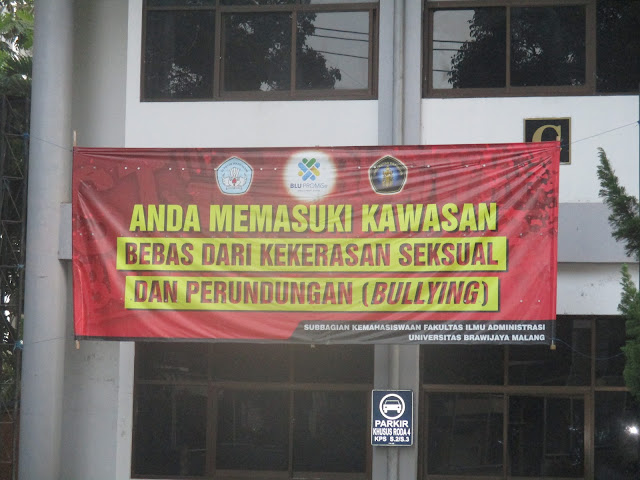

Brawijaya in East Java has more students than the unis of SA and WA combined. Its green grounds have hundreds of pennants and streamers celebrating the institution’s upcoming 59th birthday, but only one warning staff and students they’re entering an area free of sexual violence and bullying.

The sign was erected after Education, Culture, Research and Technology Minister Nadiem Makarim signed regulations to tackle campus sexual violence. One section prohibits ‘intentionally displaying one's genitalia without the victim's consent.’

Another forbids ‘taking, recording, and/or circulating photographs and/or audio and/or visual recordings which have a sexual nuance without the victim's consent.’

At first glance that all sounds reasonable, though not to the Republic's peak Islamic body, the Indonesian Ulama (Scholars’) Council, and the mass organisation Muhammadiyah.

They want the phrase ‘without the victim’s consent’ deleted arguing the regulation contradicts Indonesia’s religious culture by implying sex is OK if the parties consent. In their interpretation this legalises adultery.

(Similarly twisted logic is surfacing with the teaching of English. Puritans say learning should be limited to terms used in industry and employment lest students absorb Western cultural values and practices along with verb conjugations. The most feared infection from the Anglosphere’s vaults of vice is ‘free sex’. The puzzling phrase is always in English.)

Under Islamic law sex outside marriage is haram (forbidden) but that doesn’t mean Indonesians’ libido is any less than the rest of humanity. The birth rate is 2.3 children per woman. It used to be much higher till the government ran a major Dua anak cukup contraceptive campaign (two kids are enough) last century.

In Indonesia, there’s usually a way around rules including those imposed by religions. Adulterers keen to satisfy their passion and retain their faith find corrupt clerics who ‘marry’ them before the tryst and then offer a ‘divorce’ next morning - a system known as nikah siri (unregistered marriage). MBA is a higher degree and a pregnancy outside wedlock – ‘married by accident’.

While the government says it’s trying to tackle sexual violence it condones public floggings of unmarrieds and gays caught having naughties, along with gamblers and boozers.

As part of a peace deal negotiated in 2005 between Jakarta and the separatist Gerakan Aceh Merdeka (Free Aceh Movement), the province at the top end of Sumatra is allowed to use some aspects of shariah (Islamic law).

Amnesty International Indonesia Executive Director Usman Hamid called the punishments ‘cruel, inhuman and degrading … disgraceful and ruthless – no one deserves to be brutalized and humiliated in this way.’ In the past decade more than 500 have been caned, some sentences of 100 strokes with reports of victims collapsing.

Till recently supermarkets in Java stocked lubricants and condoms, but these items have largely disappeared (not in Hindu Bali) to appease conservatives who seem to believe the sight of contraceptives on health shelves encourages horizontal refreshment.

So far Makarim has refused to shift his position, though that may change as the Islamic heavyweights start cracking knuckles. In February, the Harvard graduate initiated a joint ministerial decree banning public schools from making jilbab (headscarves) mandatory for non-Muslim students. After howls and threats by conservatives, the Supreme Court revoked the ruling.

During a webinar last week the minister, a dollar multi-millionaire businessman co-opted by President Joko Widodo to modernise the state’s creaking and crumbling education system, said he was trying to tackle ‘a sexual violence pandemic’ on campuses, not legalise consensual lovemaking:

“The ministry does not support any acts that are not aligned with religious and moral norms. The regulation was designed to tackle a specific type of violence, which is sexual violence, with clear definitions.”

His claim that tertiary education institutions are halls of deviance came from a 2020 department survey showing 77 per cent of lecturers said allegations of sexual violence had occurred at their universities, though most acts went unreported.

What’s also propelling Makarim’s initiatives are statements by courageous women following the Me Too movement in the West. Before the pandemic claims of staff groping students were surfacing and campus authorities were slow to realise the old norms no longer fitted needs.

The latest claims getting widespread publicity come from a student at Riau University (on the east coast of Sumatra) alleging her thesis supervisor tried to kiss her in a closed office. When she complained to the department secretary she said she was told not to tell anyone.

“They laughed in my face about it,” she said. “There was no protection, no empathy for what I had gone through. They tried to protect [the lecturer] instead, without caring about what had happened.” So she made a video, posted it on Instagram and told the cops.

The lecturer retaliated with defamation proceedings claiming Rp 10 billion (AUD 955,000) in damages.

Makarim’s regulation is supposed to force tertiary institutions to develop ways to handle allegations of sexual harassment or violence. The student’s lawyer has reportedly said the case could be a turning point for the implementation of the new regulation.

Andy Yentriyani Chair of Komnas Perempuan (the National Commission on Violence against Women), backed Makarim’s moves. Like the Minister, she was also educated abroad – in London. Although KP had received only 67 reports of sexual violence on campus, she said most cases were unreported or unresolved:

“Victim blaming has been the biggest bottleneck as universities refuse to admit that sexual violation does happen.”

First published in Pearls & Irritations, 20 November 2021:https://johnmenadue.com/conservatives-undermine-push-against-sexual-violence-on-indonesian-campuses/