In praise of puppets

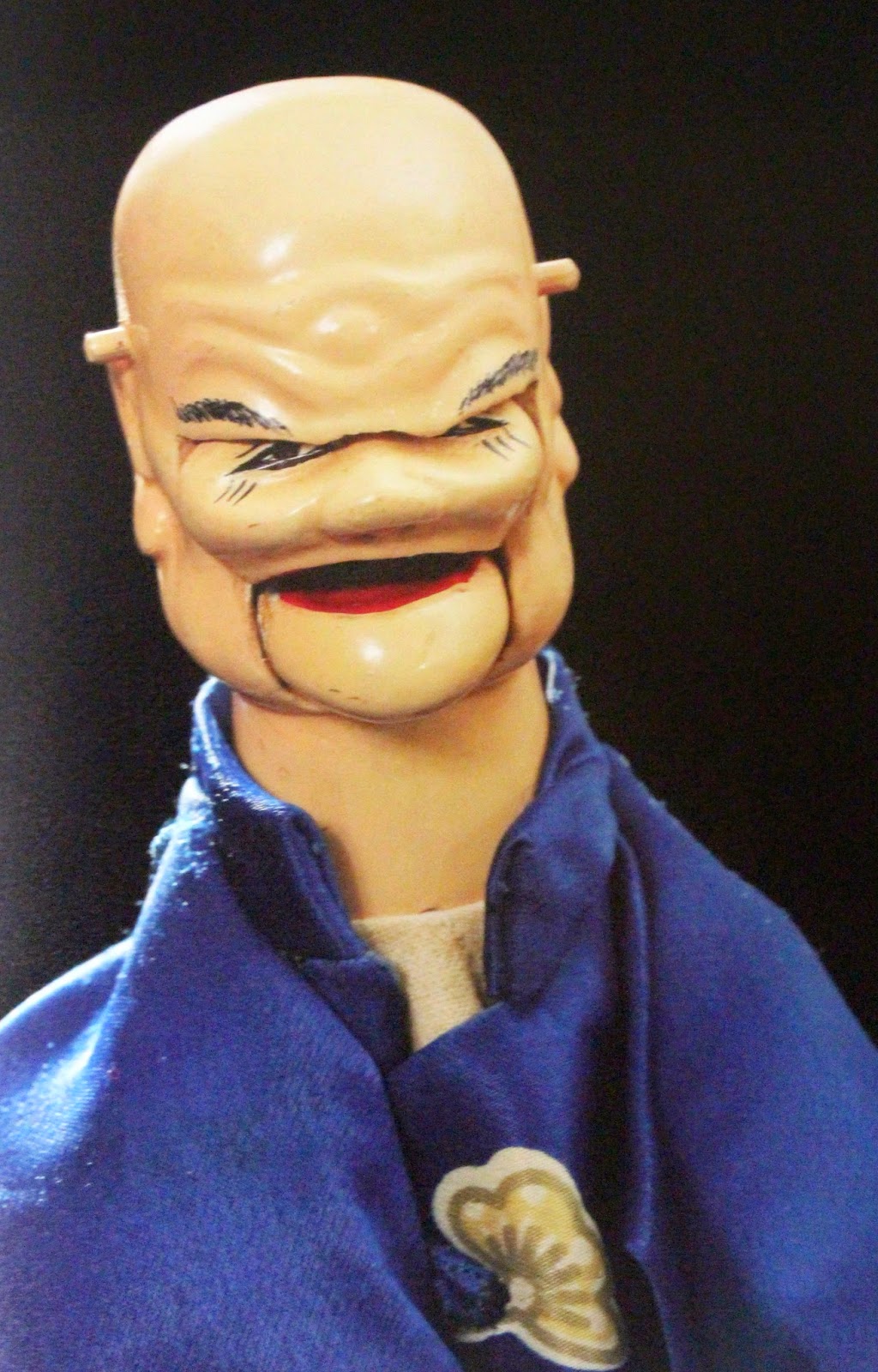

It’s easy to spot the besotted. They lavish their progeny with praise. They

dress them in the finest clothes and want to show them off, desperate to garner

praise. It’s all about one-eyed love.

This is true of parents and puppeteers; apart from the means

of reproduction there seems to be little difference. It’s a point proved by the

work of Ardian Purwoseputro, the author and principal photographer of a

splendidly illustrated text on the subject - Wayang Potehi of Java.

More scholarly

research on the glove puppets of Java may eventuate. This year the author won a

Nippon Foundation Asian Public Intellectual collaborative grant for further

study.

Whatever follows, this book will be the primary source so

all credit to the pioneer. As Purwoseputro

discovered, there’s been a dearth of information in Indonesia; the best source

to date has been in Taiwan.

The author describes himself as an independent researcher

and film maker. His interest in a

little-known art started with “childhood dissatisfaction … which suddenly

resurfaced when I watched a Potehi puppet show in early 2012.”

The location was a luxury Surabaya hotel, not the back

streets of Blitar where the young author-to-be loved the snacks and other

treats that accompanied performances.

His mother gave him a Potehi doll, but it was a cheap puppet, a little

devil, not up to the standards of those bought by his friends’ richer parents.

Nonetheless it excited his imagination and the spark

remained.

Future PhD students will have to be content with analysing

the symbols because Purwoseputro has almost sucked the topic dry of facts, adding

a fine glossary, biography and a four-page list of Potehi characters.

Wayang Potehi (also known as wayang thithi in East Java where the art remains strongest) is

believed to have come from Southern China, particularly Fujian Province. There’s

a quaint myth to explain its origins:

Four prisoners condemned to death tried to lift their depression by

performing with improvised hand puppets, using a jangle of pots and pans to

make music.

They created such a racket that warders investigated. They were astonished by the men’s spirit so

took them to the king who, of course, offered pardons with conditions: They had

to spread the art and make it popular. Variations of this story also appear in

other cultures.

Fujian is the homeland of the ancestors of the Peranakan

Chinese of Indonesia and the Malay Peninsula, according to Professor Leo Suryadinata.

In his foreword the former director of Chinese heritage at

Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University writes that Chinese law prohibited

the migration of women so the men who went overseas married locally. Their descendants (including the author)

became the Peranakan, a distinct ethnic group with its own foods and lively

hybrid culture.

Potehi based on classical Chinese stories entered Indonesia

with the migrants. It spread through

parts of the archipelago getting indigenised along the way. The earliest record

comes from Batavia (now Jakarta) in the 17th century.

Around the same time another finger-puppet show was

appearing in Britain. Punch and Judy originated in Italian culture and was

popular entertainment till recently.

Critics have condemned the violence in the stories as incompatible with modern

values.

In 1967 the Orde Baru (New Order) government introduced

Presidential Instruction 14 banning all expressions of Chinese language and culture.

This was not because the Potehi dolls were politically incorrect by whacking

each other with cudgels as in Europe, but because the Chinese were equated with

communism. To the paranoid it mattered

not that Potehi predated Mao Tse-tung by several centuries. Even the lotus

flower, a symbol of eternity, was banned.

This wasn’t the first time authorities had interfered in the

common people’s fun. In the 1750s the

colonial Dutch started taxing performances because the shows were often

associated with gambling.

Fortunately folk art rooted in the community is not so

easily eradicated by authoritarianism. Potehi didn’t perish; it hibernated.

Potehi were previously seen only in temple courtyards, locations where they

still perform. (The book includes details.)

But once Soeharto had quit the stage the puppets came out of their boxes

and into shopping malls and hotels, inspiring Purwoseputro to discover more.

The audiences and the dalang (puppet masters) were no longer exclusively

Chinese; performances had evolved and ownership had now become shared with the

Javanese.

The three-dimensional puppets are still being made and

exhibited. Purwoseputro set about finding collections and sometimes the artists

(who he calls “sculptors”), getting their stories and photographing their

creations. He also found puppets brought

from China early last century that stayed hidden from the culture cops.

Inevitably there are demons and royalty, wise men and

knockabout comics, fantasy figures all. The stories contain “heroism, romance

and tragedy, strategies and intrigues, loyalty and betrayal, as well as

humor.” Each story title is selected

after a ritual asking permission from the temple deities.

Performances are accompanied by a small orchestra that includes

string, wind and percussion instruments. The box stages are also splendid works of art.

This is an easy book to view, though sadly not to read. The text is tiny and sometimes set against

absorbing colors, a serious design error.

Try reading blue on white or vice versa and stay sane.

Described by publisher Afterhours Books as ‘a premium

coffee-table book’, it retails a shade under a million rupiah (US $84).

Indonesians may blanch at the cost, but it’s a fraction of

prices charged for books in Europe, so good value.

For example, art historian Lydia Kieven’s

inadequately-illustrated Following the Cap

Figure in Majapahit Temple Reliefs (reviewed 19 August 2013), is half the

size and almost entirely monochrome. It

was originally listed at US $142 (Rp 1.7 million).

(First published in The Jakarta Post 14 July 2014)

No comments:

Post a Comment