Sanctuary for prowlers and yowlers

Too much clutter in the house? No problem: Indonesia’s roving rombeng (junk collectors) will buy your discards. But suppose they meow? That signals a catastrophe.

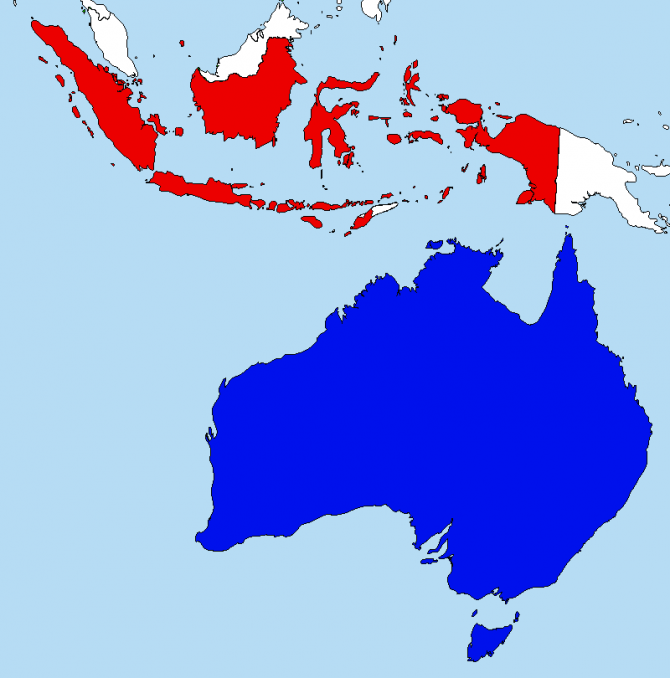

Britain and Australia have the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals The US has a similar outfit minus the prefix. Malang in East Java has Asri Rahayu Agustina (Leotina). (above)

Some cat lovers get a little unhinged, preferring felines to humans, even starting to smell and look like them. But the former fitness-center owner giving sanctuary to fourpaw refugees is no soft-touch eccentric.

Although some anti-socials among the 16 dogs are chained most of the 80 cats doze in spacious cages or wander outside and there are no odors to annoy.

“As a child I always loved animals and couldn’t stand to see them ill-treated,” she said. “I’m a Muslim and we should be caring. There’s a famous story of the Prophet preparing to pray but finding his favorite cat Muezza asleep on his clothes. Rather than disturb his pet he cut off the robe’s sleeve.

“Unfortunately few are so kind. They see a lovely cat in the market and pay thousands of rupiah - maybe up to a million (US$74) and then find looking after the animal is boring.”

In the rich character mix of Indonesian kampongs and villages there’s often a carer. Usually a woman, the pussy protector scatters scraps for the strays who soon discover Cat Cafe and call their mates.

Some see this as a humane gesture - others a curse because it encourages the beasties to stay and breed. Which they do in great numbers. Then the less sympathetic seek to cull.

The problem of controlling semi-ferals without resorting to brutal means like trapping and poisoning challenges most societies.

If someone doesn’t drown the moggy they drive to somewhere secluded far from home, then dump and flee. If they have a smidgen of compassion they offer it to Leotina.

“I usually refuse because if they took on a responsibility they should see it through,” she said. “Only if they say they’ll throw it away will I take it in and hope to find a foster home.”

Not all her charges are purrfect. There are some saber-tooth tabbies who’d be licking their chops on the sofa while the foolish family which offered refuge search for their toddlers.

Cute kittens transmogrify into ferocious toms and fecund queens. Two months after a raucous night on the tiles one becomes eight. Cats can live for up to two decades.

Abandoning unwanted pets isn’t an exclusive Indonesian issue, but elsewhere it’s taken seriously. Offenders in Western countries face fines, jail and the wrath of society.

In New Zealand ditched furballs become ruthless wildlife killers, slashing numbers of rare bush creatures and flightless kiwis - nocturnal feeders and easy prey.

In 2011 Australian live cattle exports to Indonesia were suddenly halted after a film showing abattoir workers deliberately mistreating stock was leaked to the media by activists.

Breeders claim they lost AUD $600 million and are now chasing compensation. Indonesian importers also saw their businesses slaughtered. Beef buyers faced higher prices and diplomatic dramas erupted. And all because some poorly supervised butchers saw no harm in bashing beasts that were about to be killed.

Leotina, 52, has lived in the US so knows how foreigners get angered by cruelty.

Strays handed in to shelters overseas get restored to health and microchipped before offered for sale. They are also sterilized, a practice that Leotina wants all owners to follow unless they are professional breeders.

“The offput is the cost,” she said. “Vets can charge Rp 600,000 (US $44) for a male and double for a female. I’ve had help from students training to be animal surgeons but they aren’t always reliable. It’s the same with volunteers offering assistance. Sometimes they come, oftentimes not.”

So she ends up doing much of the feeding and cleaning herself along with one worker, Suhartono to walk the dogs. His chores include carting water because the old building she uses rent-free hasn’t been connected to a supply.

The dogs have been rescued from backyard butchers. Malang is an education city with thousands of students from eastern islands where canine cutlets are a favorite.

Man’s best friends aren’t much loved in Muslim-majority Java where they’re judged unclean. So anyone dispatching a stray won’t worry the village - unless Leotina happens to be passing. Her particular gripe is with breeders who keep the trade alive.

She relies on kindhearts supplying bulk foods. She believes President Joko Widodo is a friend of animals; when Jakarta Governor he supported a ban on topeng monyet, the dancing monkeys used to entertain children.

“God sent animals to test us,” said Leotina. “We must love them all and not discriminate.”

Adopt, don’t buy

The non-profit Jakarta Animal Aid Network also urges pet shoppers to adopt, not buy.

Co-founder Femke de Haas said the network was cooperating with the national government through the Agriculture Ministry to improve animal welfare.

“There are more shelters opening, usually started by individuals,” she said. “They mean well but we need regulations and oversight on issues like cage sizes, hygiene and premises. There was a shocking situation recently when 180 dogs died in a fire.

“There can be cultural problems when people see animals as being less than humans but the situation is improving. (She has lived in Indonesia since 2002).

“Government officials agree that there should be protocols but they don’t know how these can be implemented”.

(First published in The Jakarta Post 24 January 2018)