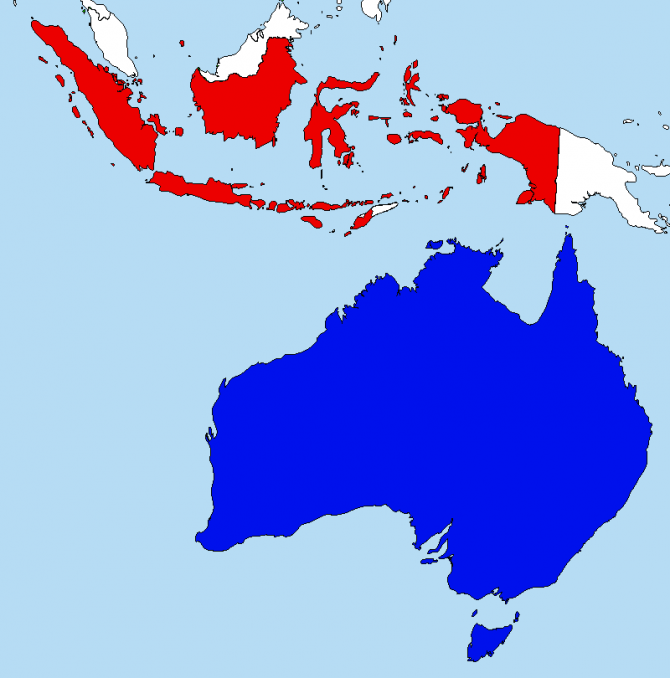

No-deal neighbours

The end-of-year deadline to conclude the Australia-Indonesia free trade talks has come and gone. Now the ambition is ‘early next year’ according to Trade Minister Enggartiasto Lukita. That will clash with the lead up to the 2019 Presidential election when parochial concerns will be more pressing than the contentious issue of concluding business with the folks next door.

It’s a pity Donald Trump didn’t lend his talents to the negotiations. The self-appointed master deal maker might have come up with the ‘most tremendously exciting best agreement ever, wonderful and big.’

But even with the hyperbolic American leader’s skills any Indonesia-Australia Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (IA-CEPA) would have been revealed as fractured once Air Force One had left the tarmac.

To say that negotiating the IA-CEPA was always going to be difficult is several fathoms below understatement so applause for those who tried hard.

Their reasoning was sound even if their understanding of the subtleties of Indonesian thinking and culture was flawed. Two countries right alongside each other. One has a growing population and shrinking farmland, the other has ample space and massive supplies of grain, beef and milk.

‘Partners in Prosperity’ sang the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry but few Indonesians joined the chorus. They need imports but buy reluctantly. Apart from the shame of having to rely on outsiders to supply the daily needs of the world’s fourth largest nation, Indonesians fear that buying essentials from afar will diminish their jingoistic claim to be an international independent power.

Kutukan means curse, now a relic word in English but throbbing in Indonesia where it’s regularly used, even in the mainstream media. It explains why things expected to come to pass fail despite propitious signs.

The IA-CEPA was doomed largely because Australia wanted the agreement more than its neighbour, even though President Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo was reported to be keen to have all documents signed by year’s end. The Javanese are skilled in telling foreigners what they want to hear, while Australians have been naive to think ‘yes’ always means what it says.

Indonesia is gripped by nationalism and its sibling protectionism. So is Australia: In April and in the midst of the negotiations Canberra slapped a tariff on A4 paper imports from Indonesia (and other countries) after the sole manufacturer alleged dumping. The company is called Australian Paper, but it’s owned by the Nippon Paper Group.

Australia also got greedy assuming that proximity gave an unassailable edge. Indonesia is now importing wheat from the Black Sea at USD 100 a tonne less than the Fremantle price, and bringing in buffalo meat from India.

There have been other neon signs flashing caution. Talks started in 2010, hibernated when the two countries were quarreling over capital punishment, then woke last year.

While Jokowi was apparently agreeing with Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull about urgency during a visit to Sydney in early 2017, back in Jakarta he was talking about ‘food sovereignity’.

The rhetoric is at odds with reality; even staples like salt and rice (Indonesia used to be an exporter) are now being elevated from bulk carriers into silos at Tanjung Priok (Jakarta) and Tanjung Perak (Surabaya). Source nations include Thailand and Vietnam.

The IA-CEPA negotiators kept smiling in public, sometimes overdoing the grins when they called a media conference in September to announce minor gains that had already been trumpeted in February.

The language also failed to connect: Turnbull spoke of a ‘high quality’ agreement while Indonesia’s lead negotiator Deddy Saleh chose the adjective ‘good’.

Australian universities want to open campuses in the archipelago - an ambition that frightens Indonesian educators who fear students will migrate to quality teaching.

What Indonesia really wants Australia can’t deliver - massive capital investments to keep Jokowi’s infrastructure projects moving. Australia is not within coo-ee of China and Japan in supplying materials and loans.

Australians also rightly fear much would be lost in a country noted for corruption and bureaucratic quagmires, and where the rule of law can be elusive.

Australians are bound by rules that don’t always bother other traders. It’s illegal for Aussies to bribe public officials anywhere.

The World Bank lists New Zealand as the number one country for doing business (Indonesia ranks 72nd) so it’s no surprise Australian investors head across the Tasman Sea rather than the much narrower Arafura Sea.

The other demand has been for jobs in Australia for nurses, maids and construction crews - extending the Republic’s people exports beyond Hong Kong, Singapore and Malaysia.

Indonesian workers are often multi-skilled, willing and prepared to live in remote areas, but few have good English or understand Australia’s rigid health and safety laws. Bali holidaymakers would have seen bare-head labourers wearing thongs scrambling up bamboo scaffolding and across work sites littered with hazards.

The work culture obstacles could be overcome with intensive training, but selling this idea in Australian states with high unemployment would generate a political firestorm. Australians will probably go to the polls in late 2018 or early 2019.

If trade talks restart next year there’s little chance much energy will be applied. Indonesia will continue to buy primary produce from Down Under, though only if it can’t get cheaper from elsewhere, and Australian traders will still complain about tariffs and other imposts suddenly levied.

This market potential is everything its boosters claim - expanding and close. What they don’t say is that it’s damnably difficult to achieve when the two sides have different expectations, agendas and cultures.

(First published in Strategic Review 22 January 2018: http://sr-indonesia.com/web-exclusives/view/no-deal-neighbors

##

No comments:

Post a Comment