Blood on the stoles: The role of Catholics in the 1965-66 post-coup

genocide

Duncan Graham*

ABSTRACT

In 2018 Australian academic Dr Jess Melvin proved what had

been long surmised - that the Indonesian military engineered the genocide following

the 1965 ‘coup’.

[1]

The Army wasn’t alone. Less well known

[2] is

that it was backed by elements of the Catholic Church.

Some had links to Australian politicians and

spies.

A key agent provocateur was Dutch

Jesuit Joop Beek who trained cadres to be fervent anti-Communists.

Their role in fomenting political, social and

personal hate cannot be quarantined from the deaths of maybe 500,000 or more real

or imagined Communists.

This is still a

deeply sensitive issue across the nation and particularly on the island of

Flores.

[3]

Around Maumere on the Northeast

coast between 800 and 2,000 Catholics were murdered by their pew neighbours

while only two priests offered last rites.

[4]

Despite earlier promising to open

discussion of the killing times, President Joko Widodo has recanted; it’s

unlikely there’ll be moves towards national healing by his government in its

second five-year term.

[5] [6]

However a truth and

reconciliation commission initiated by the Church, alone or alongside liberals

in other faiths, could start the process of restorative justice.

Through field research including

personal interviews with priests and laity, this paper will examine why some

clergy ‘failed to distinguish between throne and altar’,

[7] betrayed

their beliefs and shattered their congregations. It also asks how society can

prevent similar events recurring.

- Duncan Graham, M Phil (UWA) is an Australian

journalist living in Indonesia.

He has a Walkley Award, two Human Rights Commission Awards and several

other prizes for his work. For much of this century he’s been writing for

the English-language media in Indonesia. More details: https://www.indonesianow.blogspot.com

Note on style: Single

quotes indicate a written public reference; double quotes are from personal interviews.

Thanks: To my wife Erlinawati in Malang,

Dr Anton Lucas in Adelaide

and Dr John Prior in Maumere for reading early drafts and suggesting

corrections. However the final responsibility lies with me.

IMPORTANT TO SAY …

This paper is by an

Australian. It’s about genocide and a

particularly evil event in Flores where

Catholics slaughtered Catholics while their priests stayed silent.

It’s also about

reconciliation. Some might assume it’s

another prescription from a smug Westerner telling the neighbours what to do

because Australia

has got its past sorted.

If only. The sands of my country are also stained with

blood and only now, after more than a century, is our guilt being slowly

exposed as the truth is revealed. The

Parliament apologised to the First Australians ten years ago but has since done

little. We are still arguing about constitutional recognition. The wrongs remain. Australians are in no position to preach.

So although many individuals are

guilty for what they did – or didn’t – do, this paper is not a general criticism

of Indonesia

or the Church. The issues are universal. Rather it’s a damnation of all nations and

leaders, lay and clerical, who reject moral principles, then refuse to recognize

the wrongs of the past and work to heal the wounds.

It’s also a warning; zealotry,

tolerated to boost a seemingly righteous cause, can lead to the justification

of heinous acts that come to haunt later generations.

Human rights know no borders.

First presented at the Indonesia

Council Open Conference,

ANU Canberra, 19-21 November 2019

A Church corrupted, congregations betrayed

There’s

no power worth defending by bloodshed of the people. Abdurrahman Wahid

[8]

On most days Egenius Pacelly (EP)

da Gomez can be found reading on his verandah just outside Maumere on the road

to Ledalero. If absent he’s likely to be

in the East Flores city’s Nusa Indah bookshop looking for the latest Tempo news magazine or fresh stock.

He’s long been a widower but doesn’t

hang around mourning; the 79-year stays intellectually alert through following

national politics, though his mind often wanders back to a searing moment in

his life – Sunday, 20 February 1966. At the time he was a Catholic Party

activist and called to a meeting of Komop (Komando

Operasi) and local officials.

Attendees were told

‘instructions’ had come from Jakarta,

1,700 km to the west, to ‘secure’ all Communists and their sympathizers, and

that every political party had a quota to fill.

There were then about 2,000 people in Maumere,

[9]

perhaps ten times more in the surrounding Sikka Regency.

Many citizens knew each other if not casually

or as neighbors, then through intermarriage.

A report of the meeting and the

history of the horror that followed was produced eight years later by Anon and

titled

Menjaring Angin (To Reap the

Whirlwind).

Da Gomez, who has long been

a prolific writer and published historian, reluctantly agreed that he’s

the

author, though he says the document was later edited by others.

[10]

Two of the 130 pages are

missing.

The circumstances are mysterious.

The original Gestetner stencils were held by

a priest.

When he died his belongings

were allegedly ransacked and the document damaged.

[11]

The report concerns ‘human

beings, society and their relations with the Creator ... a search for something

that if seen clearly, might be best called meaning.’

[12]

It’s also one of the few

surviving papers giving a background to the murder of maybe up to 2,000

citizens by their fellow Catholics from February through Easter to May 1966 in

Maumere and surrounding villages.

No trials were held.

The men were usually hacked to death in

public, their friends and relatives forced to watch, the bodies kicked into

graves which are still unmarked.

[13] While

this was underway the clergy betrayed their calling by offering only last

rites.

Families still grieve and even

now fear repercussions from the Army if they speak out.

To understand how this tragedy

occurred, it’s useful to check the months in Jakarta leading to the ‘coup’

[14],

and what was happening within the Catholic Church.

To set the scene here’s The Atlantic contributor John

Hughes succinctly reporting in 1967:

This attempted coup, on the night of September

30-October 1, 1965, touched off a dramatic series of events. The Army struck

back, grinding the Indonesian Communist Party into oblivion with ruthless

efficiency. Many thousands of Indonesians were slaughtered in a nation-wide

bloodbath.

An obscure general named Soeharto was catapulted

into prominence. Indonesia

was wrenched back from a headlong leftward slide in both domestic and foreign

policy. And eventually Soekarno, the man who had cast his magic political spell

across Indonesia

for so long, was exposed, discredited, toppled.

[15]

This was at the height of the

Vietnam War when US and Australian troops were fighting a losing battle to stop

a Communist take-over of the south.

The

‘Domino Theory’ was driving foreign policy.

This imagined ferocious hordes knocking down weak states as they hurtled

towards the largely empty and resource-rich Great South

Land.

[16]

The Partai Komunis Indonesia (PKI) was then the largest in the

world outside the USSR and China, with an

estimated three million members.

Western governments weren’t the

only ones terrified of the Red wave turning into a tsunami. The Catholic Church had become obsessed with the

reach of Communism at the expense of its holy ministry, so set out to demonise

the party and its supporters. The

repercussions of this crusade have led to terrible wrongs done to individuals,

their families, communities, societies, the nation and the Church.

In Indonesia the most aggressive and

influential anti-Communist operator in the Church was the Dutch-born Jesuit

Josephus Gerardus (Joop) Beek (1917 – 1983).

He was sent to Yogyakarta

in 1938 and imprisoned by the Japanese after the 1942 invasion.

[17] He later became an Indonesian citizen.

In the early 1960s he was in Jakarta running

leadership training courses called

Kaderisasi

Sebulan (KASBUL - Regeneration Month) rousing students against Communism.

[18]

A Dutch journalist reported that Beek, who was teaching at

the University of

Indonesia:

… had already for years maneuvered

important people towards key positions within society and had collected wiz

kids around him with whom he had created

[19]student

cells.

These grew into a major

influential power.’

[20]

Film producer Joop van Wijk wrote in a promotion for his

proposed film Imitatio Ignacio that

Beek was:

…the brain behind the 1965 coup in Indonesia,

leading to his fingers being tainted with the blood of hundreds of thousands of

adversaries of dictator Soeharto. We find out how he with his ever-growing

network of followers may be regarded as the man who was by far the

best-informed man of Indonesia

in the turbulent 1960’s.

And how Joop Beek became crucially

important for western secret service organizations such as the CIA, MI5 and

ASIS in their undercover operations to support Suharto against the first

president of Indonesia Sukarno who was ever further sliding to the left.

[21]

It’s possible hardships endured during his years in a

Japanese prison camp affected the priest’s thinking. Even so he could have

justified his fanaticism by referencing the Vatican’s 1949

Decree against Communism [22]

which declared members should be excommunicated. That meant card-carrying Reds

could be excluded from participating in the sacraments and services.

It did not mean imprisonment, torture and

execution.

[23]

Beek is reported to have favoured the slogan ‘kill or be

killed’, when confronting Communism, a phrase also used by others in recalling

their experiences in 1965.

[24] How all this fitted with Christ’s teachings of

passivity, tolerance and forgiveness is unclear.

Beek was regularly talking with

Western security agencies and was close to the Australian Catholic political

activist

Bartholomew Augustine (BA) Santamaria (1915 –1998). [25] His Church and business associates funded anti-Communist

movements in Australia and Southeast Asia, and supplied Western governments with

information and advice.

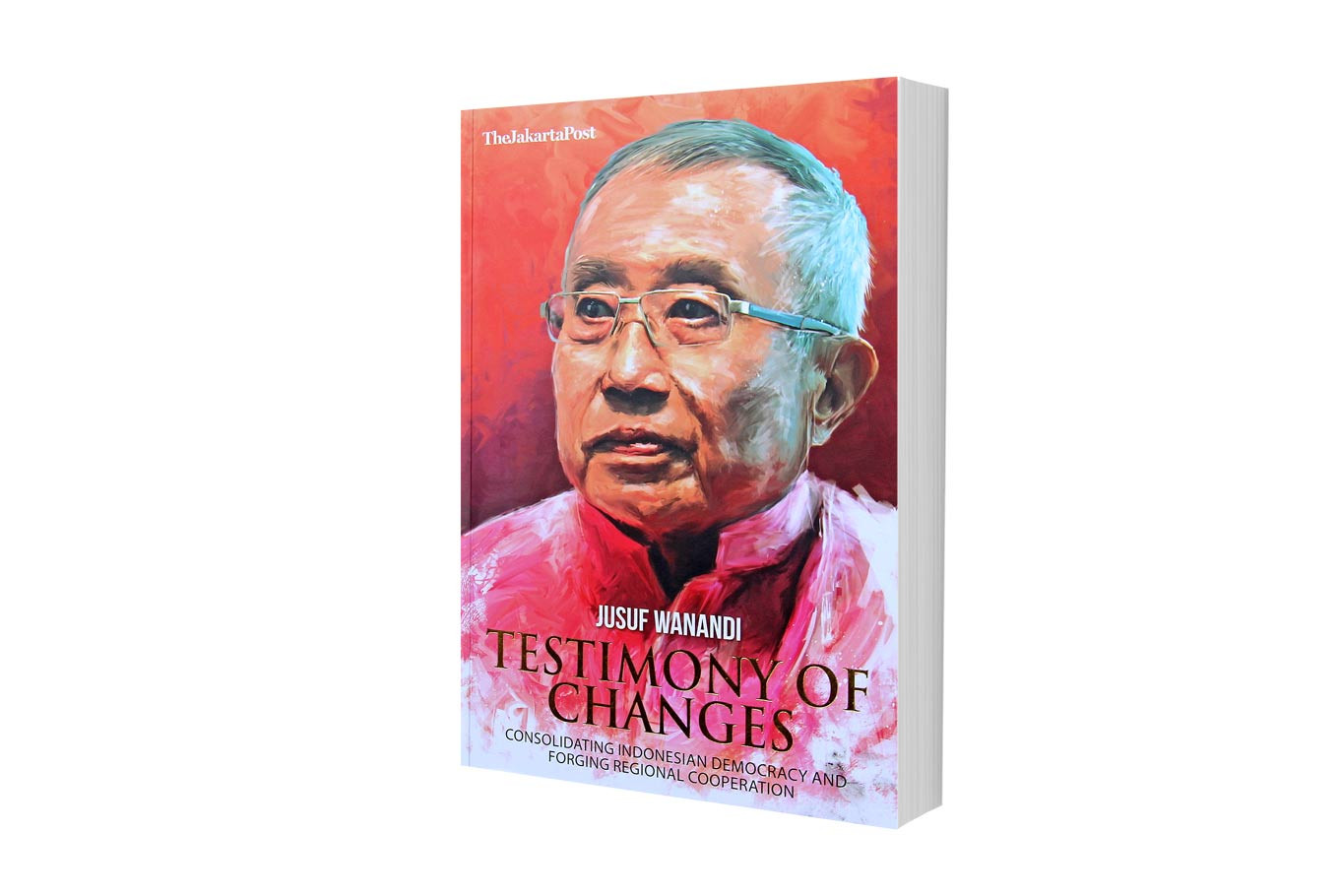

Prominent among Beek’s coterie

was Jusuf Wanandi, born Lim Bian Kie.

[26]

He’s now a major businessman, political commentator and Jakarta legend.

[27] He’s

also a complex character, harboring secrets, skirting issues, masking a

troubled conscience with regrets.

These

appear sincere, though fall short; he won’t open all the cupboards, instead

claiming the shelves and drawers are empty.

They are not.

At 82 Wanandi is spry,

articulate and a ripping commentator on the doings of Indonesia’s

political

haut monde. He’ll talk

openly on almost everything – except his guru – Joop Beek. Curiously the priest

doesn’t feature in Wanandi’s autobiography

Shades

of Grey which is otherwise filled with names and details of the author’s life

and influences.

[28]

In personal discussions two prominent Jesuits (the late Father Adolf Heuken (right) and Franz Magnis Suseno) have

confirmed that Beek and Wanandi lived close to each other in the Jakarta suburb of Menteng

in the mid 1960s, and were meeting almost daily.

[29]

Santamaria gets one sentence in Wanandi’s book:

‘Through a group led by Bob Santamaria I got

to know some influential people in Manila’.

Asked to expand Wanandi would only say: “The

efforts of Bob Santamaria had been sporadic and therefore with no lasting

effect.”

[30]

Australian

journalist Frank Mount was employed by Santamaria to work in the region; he had

close links with Beek and Wanandi who supported the bloody Indonesian take over

of East Timor, though Wanandi now has regrets.

[31]

In his autobiography

Wrestling with Asia, Mount

claims Beek set up a network of anti-Communist Catholics in Indonesia, as Santamaria had done in Australia.

[32]

In 1965 the network heard through a spy in the PKI that

Soekarno was sick so assumed dramatic action was likely by the Party.

[33]

Beek passed the information on to Australia’s security organisations.

[34]

Wanandi’s present Central Jakarta

office is in the

Centre for Strategic and

International Studies (CSIS).

The 1971

founders were Wanandi and his younger brother Sofjan, backed by Chinese and

mainly Catholic entrepreneurs.

They were

persuaded to donate

[35]

by Wanandi’s friend, General Ali Moertopo (1924 – 1984).

How that persuasion was exercised is not

known.

[36]

Today the organisation has an image of independent

professionalism, a non-profit think tank covering social, international,

political and economic issues, referenced by academics and journalists.

That wasn’t the case during Soeharto’ early years in the

palace: The CSIS was then not a lobby for human rights or a centre of impartial

research, but a propaganda arm for Soeharto’s

Orde Baru (New Order) government.

[37]

Wanandi got the CSIS into Western boardrooms, ministries

and high-level conferences through his skills as an amusing, knowledgeable, cosmopolitan

English-speaking inner-circle unofficial diplomat and ethnic Chinese Catholic –

the congenial face of a ruthless dictatorship run by dark men in khaki.

[38]

This is ironical as Wanandi later helped set up the

Kompas daily, now the most trustworthy

Indonesian language newspaper in the Republic – though originally established to

counter Red propaganda.

[39] [40]

Today the CSIS seems to have lost much of its early Catholicism.

[41] Some

female staff wear

jilbab, the Islamic headscarf. Open ties with the

military have also been cut. Said Wanandi with some vigor: “Never trust the

Army.”

[42] Yet

that’s what he was doing through his links with Moertopo.

Mount wrote:

Over the years, the more capable and energetic

members of Beek’s network gradually moved into political, commercial, academic

and government posts and many of them have now risen to positions of great

national and international importance and influence.’

[43]

Unfortunately Mount would not respond to questions about

Beek.

Snuggling up to Soeharto’s ruthless regime in its early

days has done the business interests of the Wanandi brothers no harm.

In 2007

Forbes

magazine said Jusuf Wanandi was worth US $307 million. Sofjan started the

Gemala (now Santini) Group which operates factories around the world.

[44]

Wanandi’s admiration for the Muslim Moertopo is not shared

by Western academics. Australian academic Dr Richard Tanter dubbed Wanandi a

‘former Opsus (

Operasi Khusus, Special Operations group) associate.’

[45] Opsus

was run by Moertopo and was its ‘intellectual core, which provided intellectual

cover and academic legitimation’.

The late US-Indonesia expert Dr Benedict Anderson wrote

that Moertopo's specialties

included ‘black

intelligence

operations,

deployment

of agents

provocateurs, behind-the-scenes

political

manipulations,

and

the

sophisticated

cultivation

of influential

politicians,

businessmen,

and

academics

overseas.’

[46]

Canadian professor John Roosa was more direct, writing that

Wanandi:

… laboured for years on the dark side,

helping the Soeharto dictatorship commit a variety of crimes, and he remains

proud of his work as the protégé of one of its most loathsome dirty-tricks

intelligence officers, Ali Moertopo. His insider accounts of the

decision-making behind various massacres are often self-serving and inaccurate.

[47]

Moertopo continued to have Soeharto’s ear until the soldier

reportedly died of a stroke

[48] while

taking a nap at the CSIS where a room is dedicated to his memory. The general

was Wanandi’s conduit to Soeharto and is admired “for keeping his cool”

following the coup.

[49]

Wanandi is not one of the grandees that fill the Indonesian

oligarchy. At times he can be self-effacing which helps him steer awkward

inquiries into safer streets. Like telling when he was caught by soldiers in

1965 driving a Jeep at 3 am in Jakarta

with a pistol and two Sten sub-machine guns in the vehicle.

[50]

His contacts in high places and silver tongue prevailed; he

kept driving and kept the guns, though later claimed they didn’t work.

These jolly Boy’s Own

adventures cut no ice with Roosa. In a

review of Shades of Grey published in the Australian quarterly Inside

Indonesia he wrote:

Wanandi’s account shows how closely the student movement worked

with the Army. The students knew in early October that they were in no danger.

The PKI put up no resistance as they rampaged through the streets, ransacking

and burning houses, offices, and schools.

But still they pretended as if they were brave heroes at

war risking their lives. Wanandi notes in passing, without an expression of

regret, that the students of the Indonesian Student Action Front (KAMI) forced

people to join their demonstrations.

[51]

When invited to respond Wanandi commented in writing: “I

have not read the review of Roosa’s (sic) and (I’m) not interested in his

opinion.”

[52]

Well into the 21st century it’s difficult to understand the

depth of hatred towards Communism in the 1960s – not just from the capitalist

US and its allies including Australia,

but from the Catholics and their Church with its ambiguous approach to human

rights and support for despots like Soeharto.

In his autobiography Wanandi calls the genocide ‘the most

abominable episode in our country’s history’.

[53]

However he’s less than frank about the role he and his colleagues played,

raising the question: Did the Catholics go too far in promoting hate?

Do they have blood on their hands?

Wanandi:

President Soekarno bore the first

responsibility ... because he was still full president then ... we were

activists during that period and heard about the killings, but because of the

political uncertainties we did not react to those barbaric acts.

Do you ever look back - do you think because Catholics were

so opposed to the PKI that you were in any way responsible for the bloodbath?

=That’s not so, because we warned

Soekarno ... on the 14 November (a deputation) went to Soekarno and

informed

him that he had to do something

... we knew some parts of it (the genocide) but we had no inkling of the

intensity in East Java, and Central Java and Bali till afterwards.

[54]

Yet declassified files

from that period released by the US Government in 2017 show the killings were

widely known. [55] The hierarchy of the Church was also aware. Letters have come to light dated 6 November

1965 and 6 January 1966, weeks before the Flores massacre, forbidding Catholics

from being involved with the Army Para Commando

Regiment which was carrying out the killings in Java and Bali.

[56]

What more could Wanandi and his students have done to stop

the slaughter? As Catholics, where was their moral responsibility? Wanandi:

We were the first targets of the PKI. It

was kill or be killed. We were more anti-PKI than anyone else, always the first

ones ... Muslims came later.

Only the Army

opposed.

[57]

The sensitivity now of human rights was then

of a different intensity.

Who cared

about human rights at that time?

It (the

Universal Declaration of Human Rights) was not adopted by the UN until 1948.

[58] We

were not responsible for the bloodbath.

Soekarno and Soeharto share (responsibility for that).. . lacuna of

authority.

[59]

Wanandi and other conservative Catholic leaders in Jakarta would have been

aware of the awful events in Maumere involving the clergy and their

congregations. The slaughter started in February 1966 after the killings had almost

petered out elsewhere, yet no mention in Shades

of Grey.

It took time for the sins to be recognized and the remorse

to mature.

In his autobiography Wanandi

calls for a

Truth and Reconciliation

Commission, like the South African restorative justice process

last century following the destruction of apartheid.

[60]

So far little has happened.

While running for the presidency in 2014 Joko

Widodo appeared to support an inquiry, but recanted once in office

[61] as retired generals claimed that

Communists were organizing a comeback, vigilance must be intensified and the

defence budget boosted.

[62]

The scares began to get traction,

spooking Widodo who was also subject to smears alleging he’d been a Communist.

[63] To

blunt these attacks he appeared on television watching the ghastly 1984

agitprop

Pengkhianatan G30S/PKI (Communist

treachery of 30 September).

This crude piece of cinema has been compulsory

viewing for schoolchildren every year on the anniversary of the ‘coup’. The President even suggested the film be

updated. [64]

Unless they’re well read and in a family of liberals,

today’s youngsters remain historically illiterate about their nation’s recent past

which has been largely researched by Western academics working overseas; their

books are usually expensive, difficult to obtain, and in English. [65]

An exception is Dr John Prior, a

British-born priest with the Society of the Divine Word. He came to Eastern Indonesia in 1973 and is now in Maumere.

He’s written scholarly papers and co-edited a

collection of essays in Indonesian on the events in East

Flores.

[66]

He’s tried to analyse why the priests

went along with the Army’s slaughter and concludes the clergy had become snared

by power, enjoying the prestige of being close to the government through its

purge of Communists: ‘The Church ran adrift from the concerns of the

surrounding society.’

[67]

The 2003 Catholic Bishops’

Conference in Jakarta referred to ‘the decoupling of faith from daily life’

[68] This

began much earlier when the Church became obsessed with fighting Communism and

forgot that its mission was to guide and protect its flock.

The hate was not exclusive to Indonesia.

[69]

Priests allowed themselves to be lured

from their responsibilities to ordinary parishioners through playing with State

power, and financially benefiting from siding with killers. They’d been indoctrinated through strident

Catholic political propaganda, largely driven by foreign priests like Beek.

They argued that Communism was so

satanic killings were justified even though this ran counter to their

consciences and all Church teachings. This moral code would have been known by

every novice.

They didn’t differentiate between

Communist ideology, open to challenge through better ideas, and those who liked

some of the party’s policies such as land reform though were not card-carrying

members. It was easier to kill than

change minds.

What has to change to avoid a

repetition? Wrote Prior:

Their (the

clergy’s) mission to save souls was buttressed by a spirituality that

encouraged people to endure the trials of this world while patiently trusting

in God’s mercy in the next … they failed to distinguish between throne and altar

…

We need to

untangle the pastoral strategies of the Church community from the

unevangelical, self interested, repressive, patriarchal policies of the

governing elite.

[70]

Does the Church have blood on its

hands?

Prior did not hesitate:

“Yes.”

[71] And

da Gomez who features at the start of this paper?

“We need reconciliation.

The initiative must come from the Church. The

children must be educated.

To stop this

happening again all Indonesians must know the true history of their country.”

[72]

CONCLUSION

The past is never where you

think you left it. Katherine Anne Porter [73]

The ‘coup’ occurred two decades

after the end of World War 11 when the Nazi party converted a largely Christian

country into a nation of hate against the Jewish minority.

According to one historian Nazism

sought to ‘transform the subjective consciousness of the German people—their

attitudes, values and mentalities—into a single-minded, obedient ‘national

community’.

[74] This was the process engineered in Indonesia in

1965.

Zealotry is dangerous, doubly so

when faith-based. The common view is

that religious fundamentalists are simpletons driven by monochrome assumptions,

mindlessly led by smarter demagogues indifferent to the consequences of their

actions.

Yet the Jakarta Catholics

associated with the ‘coup’ aftermath were well-educated, intelligent

individuals. They knew European history.

How could they have been so influenced by Beek and the villainy of his ideas that

they abandoned their personal moral values taught by their church.

One answer is distasteful: Some had

other agendas, aware that if they picked the winners in the chaos then they’d

benefit financially and personally – if they didn’t they’d be in mortal peril.

Choose wisely or perish.

[75] [76]

The Catholics were in a minority,

about two per cent of the national population.

The Chinese constantly suffered discrimination and knew they’d not

survive without powerful patrons. The regrets being expressed today might carry

more weight if those pleading for understanding were remorseful thugs realizing

their earlier errors. They weren’t.

Western governments were also

culpable. They were aware of the

massacres through reports by journalists and diplomats, but chose to ignore the

genocide because it halted the spread of Communism through the archipelago. No-one comes out of this story unscathed,

though one priest can still stand tall.

Near Maumere Father Frederikus

Pede da Lopez challenged the military’s orders and demanded his congregation in

Wolokoli be released.

So the Army

contacted his bishop and da Lopez was moved to a seminary.

[77]Although

his protest failed he didn’t die for his defiance.

[78]

This showed the cowardice of his colleagues who used the

defence of ‘we’ll be killed if we don’t cooperate’. Sainthood was available,

but declined. Commented Prior: “They were all Simon Peters.”

The survivors’ counter argument

runs: ‘You don’t understand what it was

like – you weren’t there. Easy to sermonise now.’ True enough; none of us know

how we’d respond when suddenly faced with great moral dilemmas while fearing

for our lives.

In this case the story is not

about a few weak individuals, but almost all members of an institution built on

the principles of sacrifice and love for humanity.

[79] Where were the dissenters?

According to two historians:

A strong stand

by the Church might well have halted or at least diminished the slaughter …

most clergy stood aside as silent bystanders.

The population was cowered for over twenty years; voices for justice

remained mute.

[80]

There seems no excuse for priests

who’d taken holy orders and were supposed to have been drawn to their calling

by Christ’s offering of himself for crucifixion.

They knew what was happening and that it was absolutely

wrong. When they donned the cassocks, stoles and crucifix they took on a special

responsibility to their congregations.

[81]

Prior quotes Martin Luther King Jr:

The ultimate measure of a man is

not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands

at times of challenge and controversy.

[82]

Should such evil times return

we’ll all need to recognize and repel the seducer - hate. This can come, as it

did in Indonesia

in 1965 – 66, in the guise of a forked-tongue government claiming its motives

were altruistic, and an amoral Church compliant in the genocide.

The government’s failure to

initiate reconciliation leaves the way open for the Church to start the process

– and help wash itself of sin.

German Jesuit Karl Rahner wrote:

‘The number one cause of atheism is Christians. Those who proclaim Him with

their mouths and deny Him with their actions is what an unbelieving world finds

unbelievable.’

[83]

[2] There

are no references in Melvin’s book.

[3] The

people of Flores pay great respect to the

dead.

Many have graves in the yards and

gardens of their houses.

Not knowing

where the remains of their fathers, husbands, sons and brothers lie is a never-ending

trauma for the families. Maumere has memorials to the 2,500 who died in the

December 1992 earthquake and tsunami, but nothing to remember the pogrom.

The figure of 500,000 killed in the pogrom is clearly a

rough guess.

One estimate given to Soekarno

was 78,000 – later it had another zero added. Commander Sarwo Edhie

(father-in-law of sixth President SBY) is alleged to have said the number was

three million.

See:

Kolektif

Info Coup d'etat 65 :. - Dokumen

If correct that represents three per cent of the population at the time.

[4]

Aritonang, Jan Sihar, & Steenbrink, Karel:

A history of Christianity in Indonesia,

2008, Brill.

pp 253-255.

See section:

The tragic betrayal of 1966.

[6] See below for an account of Human Rights activist

Soe Tjen Marching questioning the

President: ‘He stated that he still did not really understand what happened, and

that this kind of thing took time. In

short, he answered my question without actually answering it. It strikes me as

pathetic that a president who is supposed to be ‘reformist’, claims that he

does not know much about one of the biggest genocides the world has seen, that

happened in his country. The deputy head of Komnas HAM told CNN that Komnas HAM

had sent its report and recommendations on the matter to Jokowi on 10 December

2014. Yet, Jokowi told me he had not seen it.https://www.insideindonesia.org/interview-with-an-activist-soe-tjen-marching

[7] Prior,

John:

The Silent Scream of a Silenced History. Part Two; Church responses. Exchange 40,

2011.

[8] Gus Dur

on quitting the presidency in 2001.

[9] Van

Klinken, Gerry:

Postcolonial Citizenship in Provincial Indonesia, 2019, Palgrave

Macmillan.

[10] The

document has not been published and only a few photocopies are available.

[11]

Conversation with da Gomez, Maumere, May 2019.

[12]

Translation by Dr John Prior SVD.

[14] I use

quotes around the word ‘coup’ because it’s still unclear whether this was a

clumsy attempted takeover by the PKI, or staged by elements in the military to

trigger a purge of Communists.

These

questions are important but not part of this paper.

[17] He was

also interred for some months by the Indonesian revolutionaries distrustful of

the Dutch..

[18] He

seems to have been Indonesia’s

version of the US Red witch-hunter Senator Joseph McCarthy (1908-1957) minus

the political authority.

[19] Beek

was involved and important but this claim is too wide.

The main actors were the PKI and the

Army.

See John Roosa in

Inside Indonesia, 24 Jan 2010.

[20] Dutch

TV-reporter Aad van den Heuvel

worked for KRO Brandpunt news and

says he met Beek in Indonesia

several times. His novel

Stenen Tijdperk

(Stone Age) has a character based on Beek. At one visit, van den Heuvel recalls

speaking with the Jesuit late in the sixties about a speech Soeharto would be

giving later, and asked Beek if he knew what it would be about. 'I don't know,

I'm still writing it', Beek replied.

Source:

https://wikivisually.com/wiki/Joop_Beek

A Dutch film about Beek was proposed.

The blurb reads:

IMITATIO IGNACIO –

CONFESSIONS OF A JESUIT PRIEST

In the second half of the last century an impoverished boy from Amsterdam becomes a

traumatized Jesuit priest. As a true Rasputin he grows into being one of the

most powerful men in postcolonial Indonesia. Driven by his obsessive

religious zeal he is the brain behind the blood stained coup of 1965 in Indonesia and

its legacy of massacres and terror.

On his deathbed Joop Beek looks in a feverish dream back on his life and the

consequences of his actions. A quest for answers to the impossible question of

‘why?’

http://in-soo.com/category/in-production/

[22]

Excommunication did not apply to all who voted for Communists or supported the

party, only to people who held the materialistic and atheistic doctrines of

Communism.

See

The Tablet, 6 August, 1949. ($)

[24]

‘

…in light of the PKI’s evil plans, there was no choice but to kill or be

killed.’ It is hard to believe that such language—especially coming from people

in positions of authority—would not have incited or at least given licence to

real acts of violence, including killing. Indeed, most accounts of the killings

by perpetrators emphasize … they had no choice but to crush the PKI.’ Robinson, Geoffrey: Journal of

Genocide Research Volume 19, 2017 - Issue 4.

[25] A determined anti-Communist Catholic,

Santamaria founded the National

Civic Council and the Democratic Labor Party in 1955. Known as The

Split, it kept the Australian Labor Party out of office till 1972. His Asian venture was called the Pacific

Community.

[26] Within a year of seizing power in 1965 the

ever-suspicious Soeharto ordered ethnic Chinese to change their names, implying

they were non-pribumi (not

nationalists) suggesting they were closet Communists; Wanandi says he did so

voluntary in a bid for recognition and assimilation, but in fact he and his

colleagues had no choice. Wanandi went

even further. He and his younger brother

Sofjan (Lim Bian Khoen) left the Catholic Party and later joined the Golkar

Party, as member of the non-democratic vehicle for keeping Soeharto in power.

[28]

Wanandi e-mailed me 16 November 2018: “Father Beek has been

the … Chaplain of the Catholic students in Yogyakarta and Jakarta later also for Catholic

scholars. He was the director of documentation Bureau of the Council of

Bishop’s of Indonesia.

As such his ideas were influential to those groups.”

[29] Father

Franz Magnis-Suseno SJ and Father Adolf Heuken SJ.

Personal interviews in October 2018. Neither

is mentioned in

Shades of Grey.

[31] Roosa,

John.

Inside Indonesia,

May 2003: ‘He (Wanandi) led the international PR campaign justifying the 1975

invasion of East Timor but then lamented the

Army’s brutal counter insurgency tactics.’

[32] Mount,

Frank:

Wrestling with Asia, Connor Court

2012.

Mount pours on his admiration for

Beek ‘a man of the people with powerful intellect … I was in thrall from the

first moment I met him.’ (P 253).

[33]

Soekarno was ill and died in 1970 of kidney failure aged 69.

[34] Wanandi

said his contacts knew Soekarno was sick and that doctors had been brought in

from China

to conduct treatment.

This news

heightened the expectation that something was about to happen.

[35] In

Shades of Grey (P111) Wanandi writes

that Moertopo ‘just called up a few

cukong

(patrons) and said ‘

tolong bantu

(please help) and that was all that was needed.’

[37] For almost two decades after the coup Wanandi and his

friends claimed they were palace whisperers, advising Soeharto. The relationship collapsed in the mid 1980s

when they suggested he step down. Their

position was taken by the Minister for Technology and Research (later to become

Vice President) Bacharuddin Jusuf (BJ) Habibie’s Ikatan Cendekiawan Muslim

Indonesia, (ICMI) Indonesian Association of Muslim

Intellectuals. It was supposedly set up

to fight poverty and improve education, but was more likely a device to counter

the CSIS influence.

[38] The CSIS was so well funded that it ran a prolonged PR

campaign across the US

to try and convince government officials and academics that Soeharto’s

oppressive government was legitimate and progressive.

[39] The paper was started in June 1965 by the Catholic

Party to offset Communist propaganda, and at the behest of the Army. The name was suggested by Soekarno. Wits dubbed it Komando Pastor because of

the Catholic connections.

[40] The

organisation also advocated against independence for East Timor and was

involved in preparing the ‘Act of Free Choice’ Indonesian takeover of West Papua.

[41] Wanandi

told me he had ceased to attend Catholic services following the findings of the

2013 – 2017 Australian

Royal Commission into Institutional Responses

to Child Sexual Abuse, and clerical pedophilia revealed in the US,

Canada and elsewhere.

He said he now

worships with the Lutheran

Church.

[42]

Personal interview 19 October 2018.

[43]

Mount: Wrestling

with Asia. Although he details countless

meetings with Wanandi and Beek, Mount gets no mention in Shades of Grey. Three requests to interview Mount made through his

Australian publisher got no response.

[44] An Oxfam report claims: In the past

two decades, the gap between the richest and the rest in Indonesia has grown faster than in any other

country in Southeast Asia. It is now the sixth

country of greatest wealth inequality in the world. Today, the four richest men

in Indonesia

have more wealth than the combined total of the poorest 100 million

people. https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/towards-more-equal-indonesia

[45] Tanter,

Richard:

Intelligence Agencies and Third World Militarism.

PhD thesis, Monash University,

1981.

[46] Anderson, Benedict: Scholarship on Indonesia

and Raison d'Etat: Personal Experience.

Indonesia

62, 1996

[48] Another

version has him succumbing to cancer.

[49]

Personal interview 19 October 2018.

[50]

At the time Stens were the

weapon of choice for insurgents. “They’d been put there by someone else. I

didn’t even know how to use them,” Wanandi said.

[51] Roosa,

John:

Pretext for Mass Murder: the September 30th Movement and Soeharto's

Coup d'état in Indonesia

University of Wisconsin Press, 2006.

[52] E-mail

correspondence 16 November 2018.

[53]

Wanandi, Jusuf:

Shades of Grey, Equinox, 2012.

[54]

Personal interview, 19 October 2018.

[56] Two

one-page letters have recently come to light thanks to Yogyakarta

lecturer Dr Baskara Wardaya SJ at Santa Dharma University. The one dated 6

November 1965, allegedly from C Carri SJ, the Vicar

General

of the Archdiocese of Semarang (Central Java)

reads: Priests and clerics are not

allowed to be part of the Panitia Pemeriksa

/ Penjelidik jang akan dibentuk oleh R.P.K.A.D.

(Resimen Para Komando Angkatan

Darat – Army Para Commando Regiment. This was the command involved in the killings

in Java and Bali. The second, dated 6 January 1966, apparently came from Justinus Darmojuwono 1914-1994 (who later became a Cardinal)

[57] Dr

Frank Palmos was one of the few Western journalists in Jakarta at the time.

He recalled that Jakarta in 1965 was "pregnant with

danger". "It is hard to exaggerate the dangers for Europeans,"

he said. The PKI made gruesome signboards depicting foreigners being bayoneted.

China

and the PKI were urging president Sukarno to allow workers and peasants to

carry arms and become a fifth force. "It was a very tense time … it was

very violent. Civil war was certain."

Sydney Morning Herald, 3 Oct,

2015

[58] This was 17

years before the Indonesian ‘coup’. In

1950 Indonesia

joined the UN and was theoretically bound by its human rights provisions.

[59]

Personal interview, 19 October 2018.

[60] Shades of Grey, P 80.

[62] No

credible evidence was ever published to support the claims.

[63] The President was four when the ‘coup’ occurred and

the party banned.

[65] In

early 2019 Dutch academic Gerry van Klinken published on Maumere.

See endnote 6.

In personal communications (May 2019) he said

there were plans to translate into Indonesian, though these may take months to

eventuate..

[66] Prior, John:, & Madung, Otto Gusti, eds: Berani, Berhenti, Berbohong (Dare to

stop lying). Penerbit Ledalero, 2015.

[67] Prior,

John: T

he Silent Scream of a Silenced

History Part Two; Church responses. Exchange 40, 2011.

[69]

‘Communism was never popular in America,

and no American group was more fervently anti-Communist than the Catholics. The

American bishops, like the Vatican,

had condemned Marxism before 1900 for its atheism, its violation of natural law

principles, and its theory of inevitable class conflict. They condemned the

Russian Revolution of 1917 that brought Lenin and the Bolsheviks to power. They

condemned American Communism in the 1930s for its adherence to the Moscow party line, its

frequent about-turns of policy, and its support of the anti-Catholic

Republicans in the Spanish Civil War.’

Source: Patrick Allitt,

Catholic

anti-Communism https://www.catholicity.com/commentary/allitt/05744.html

[71]

Personal communication, May 2019, Maumere.

[73] US journalist

and author 1890 - 1980

[74] Kershaw, Ian; The Nazi Dictatorship: Problems and

Perspectives of Interpretation; Oxford

University Press, 2000;

pp. 173–74. The Indonesian military

coined the term Gestapu for the

‘coup’ knowing its similarity to Gestapo.

[75] Wanandi

helped set up Soeharto’s Golkar Party which became an enemy of democracy.

He also became a Golkar politician and

enjoyed the president’s patronage till the mid 1980s.

[76] Melbourne University

academic Dr Justin Wejak said Pemuda

Katolik (Catholic Youth) in Flores and the surrounding

islands, like Pemuda Pancasila elsewhere in Indonesia, were involved in the

killing of local suspected communists. My father was also forced by the local

Army (KOMOP) in Lembata to become the algojo (executioner), an

involuntary involvement that he silently regretted. His PhD thesis was: Secular, religious and

supernatural: an Eastern Indonesian Catholic experience of fear

(autoethnographic) reflections on the reading of a New Order-era propaganda text.

Personal correspondence, 18 May 2019.

[77] The

Ritapirit (sometimes spelt Ritapiret) Seminary and then Ndona parish, 150 km

from Maumere.

[78] Details:

Aritonang, Jan Sihar, & Steenbrink,

Karel:

A history of Christianity in Indonesia, 2008, Brill.

pp 253-255.

[79] Two

one-page letters have recently come to light thanks to Yogyakarta

lecturer Dr Baskara Wardaya SJ at Santa Dharma University. The one dated

6 November 1965, allegedly from C Carri SJ,

the Vicar

General of the Archdiocese of Semarang (Central Java) reads:

Priests and clerics are not allowed to be part of the Panitia Pemeriksa / Penjelidik jang akan

dibentuk oleh R.P.K.A.D. (Resimen Para Komando Angkatan Darat –

Army Para Commando Regiment. This was the command involved in the killings

in Java and Bali.

The second, dated 6 January 1966, apparently came from Justinus Darmojuwono 1914-1994 (who later became a Cardinal)F

[80]

Aritonang, Jan Sihar, & Steenbrink, Karel:

A history of Christianity in Indonesia,

2008, Brill.

pp 253-255.

[81]

The

Societas Verbi

Divini (SVD - Divine Word Society) through its Sekolah Tinggi Filsafat Katolik

(College of Catholic

philosophy) at Ledalero, just outside Maumere in East

Flores, claims it is now the world’s largest trainer of SVD

missionary priests. On its website is a

quote from the German Jesuit Karl Rahner (1904-84) saying: ‘The number one

cause of atheism is Christians. Those who proclaim Him with their mouths and

deny Him with their actions is what an unbelieving world finds unbelievable.’

[82] Sermon

at Ebenezer Baptist

Church, Atlanta, 30 April 1967.